Purchase your online ticket at the best price and avoid queues

Values of the Cave

Biology

With over five million years of history, the Nerja Cave is an impressive geological spectacle resulting from karstification, creating fascinating speleothems and providing crucial scientific data. Recognized internationally, this cave stands as an invaluable scientific resource and an underground natural museum.

Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology BiologyBiology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology Biology

Fauna

Bats are the most representative animals in caves, but they are not the only ones. In the deepest part of caves, there is a peculiar and highly vulnerable fauna known as troglobia, perfectly adapted to the extreme underground environment.

Due to the absence of light and the high ambient humidity, troglobites often exhibit reduced or lost eyes, thinning and depigmentation of the outer cuticle, elongation of the body and appendages, and enhanced tactile and chemical sensory organs. Food scarcity and the need to conserve energy favor a highly varied diet and their ability to withstand fasting. Adult specimens are usually very long-lived, with a slow-paced life, frequent periods of dormancy, and the absence of daily and annual rhythms. When they reproduce, the eggs are small, scarce, and have slow embryonic development.

The troglobite fauna of a cave typically includes endemic species, meaning exclusive to the cave, which represent a resource of great scientific value. From a biogeographic and evolutionary perspective, some species are considered paleoendemics, meaning they are relics of a mostly extinct fauna.

Among the troglobites inhabiting the Cueva de Nerja, the following have been identified: the beetle Platyderus speleus (Cobos, 1961), the orthopteran Petaloptila malacitana (Barranco, 2010), the pseudoscorpion Ephippiochthonius nerjaensis (Carabajal Márquez, García Carrillo & Rodríguez Fernández, 2001), the diplura Plusiocampa baetica (Sendra, 2004), and the isopod Porcellio narixae (Cifuentes, 2018), with the latter three species also being endemic to the Nerja cave.

Cobos, 1961

Barranco, 2010

Carabajal Márquez, García Carrillo & Rodríguez Fernández, 2001

Sendra, 2004

Cifuentes, 2018

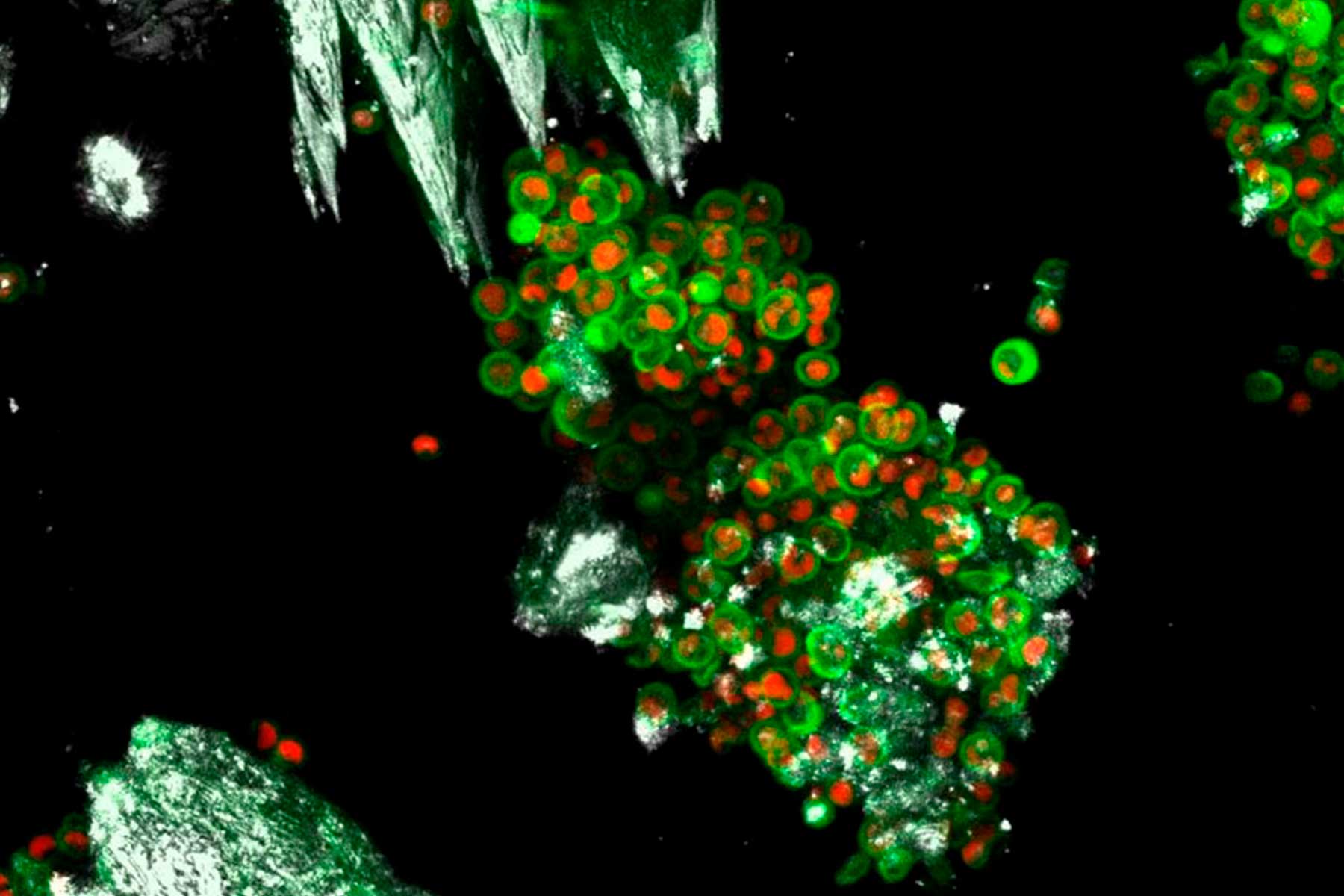

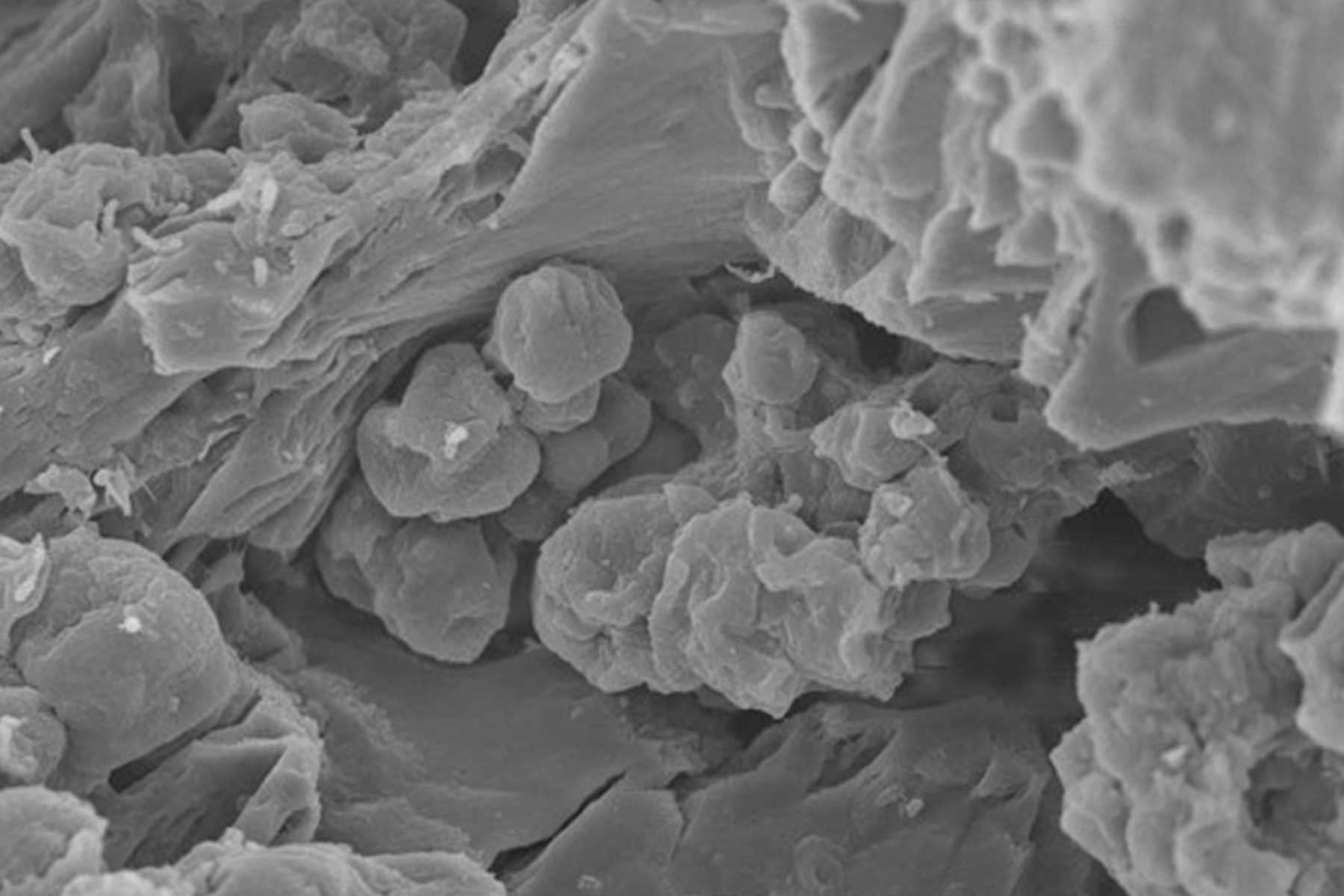

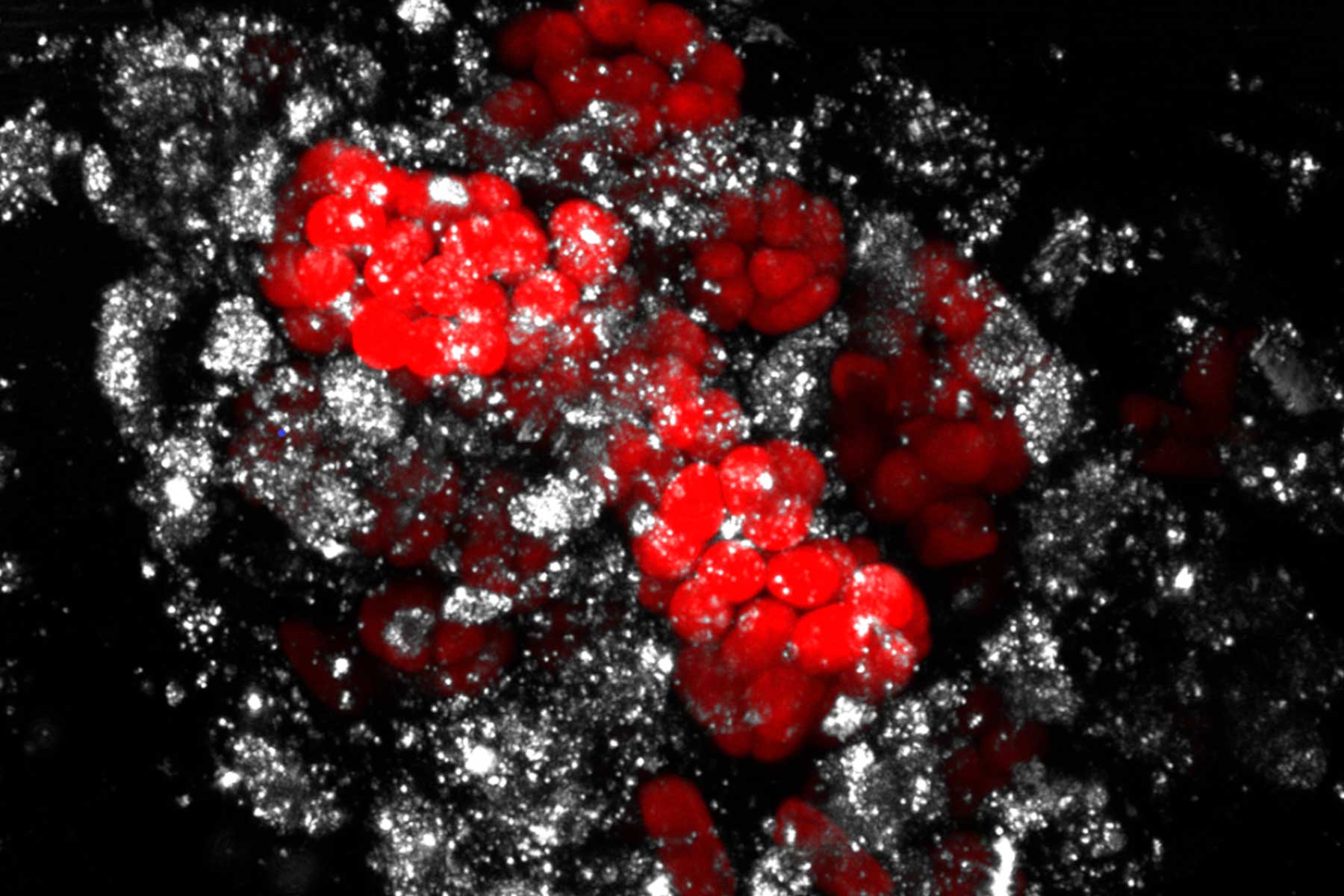

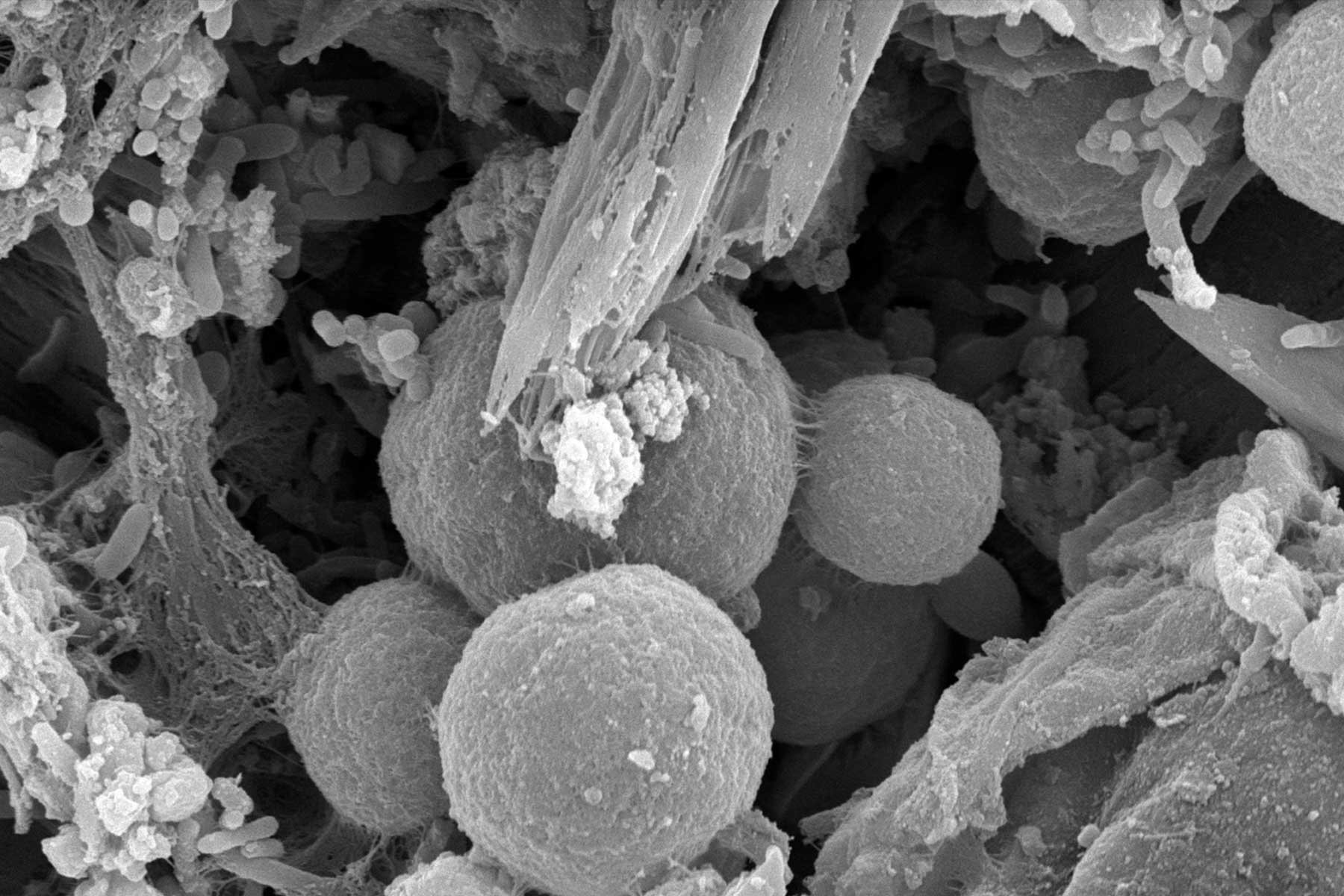

Microbiota

Microorganisms are the first living beings to colonize caves, which they can access through fissures in the rock or be transported by infiltrating water, air currents, or other living organisms. Typically, they form functional communities of varying complexity known as biofilms. In addition to organisms with diverse metabolisms, biofilms also consist of water and a hydrated matrix of extracellular polymeric substances that protect them from adverse environmental conditions and allow them to adhere to substrates. The Cueva de Nerja serves as the ecological niche for a wide spectrum of biofilms that are often not very diverse, with a simple structure and highly sensitive to environmental changes.

The balance between the different groups of microorganisms that make up the microbiota of the underground environment, as well as their relationship with the cave itself, influences the evolution and conservation of this fragile ecosystem.